The 10,000 faces of TikTok

How one little app became the vector for all our social preoccupations

The US Supreme Court ruled today that Congress could outlaw TikTok, a predictable decision that puts two presidents in the awkward position of scrambling to save it. Dearly departing President Joe Biden now says he won’t enforce the ban, though he signed the underlying bill into law. Incoming President Donald Trump, meanwhile, has vowed to keep TikTok in the US, after griping and groaning about “the Chinese app” for much of his first administration. Just four years ago, Trump issued a unilateral TikTok ban that called the app an urgent “threat.” Now, he says, there’s “a lot of good” there: “a lot of people on TikTok that love it.”

Generally, I wouldn’t make too much of this Trumpian self-own. Trump is, among other things, a pretty … fair-weather … policymaker. But the curious duality of his views on TikTok — a platform he has called, in a single sentence, simultaneously good AND bad — reinforced a theory I’ve been nursing about the imperiled short-form video app.

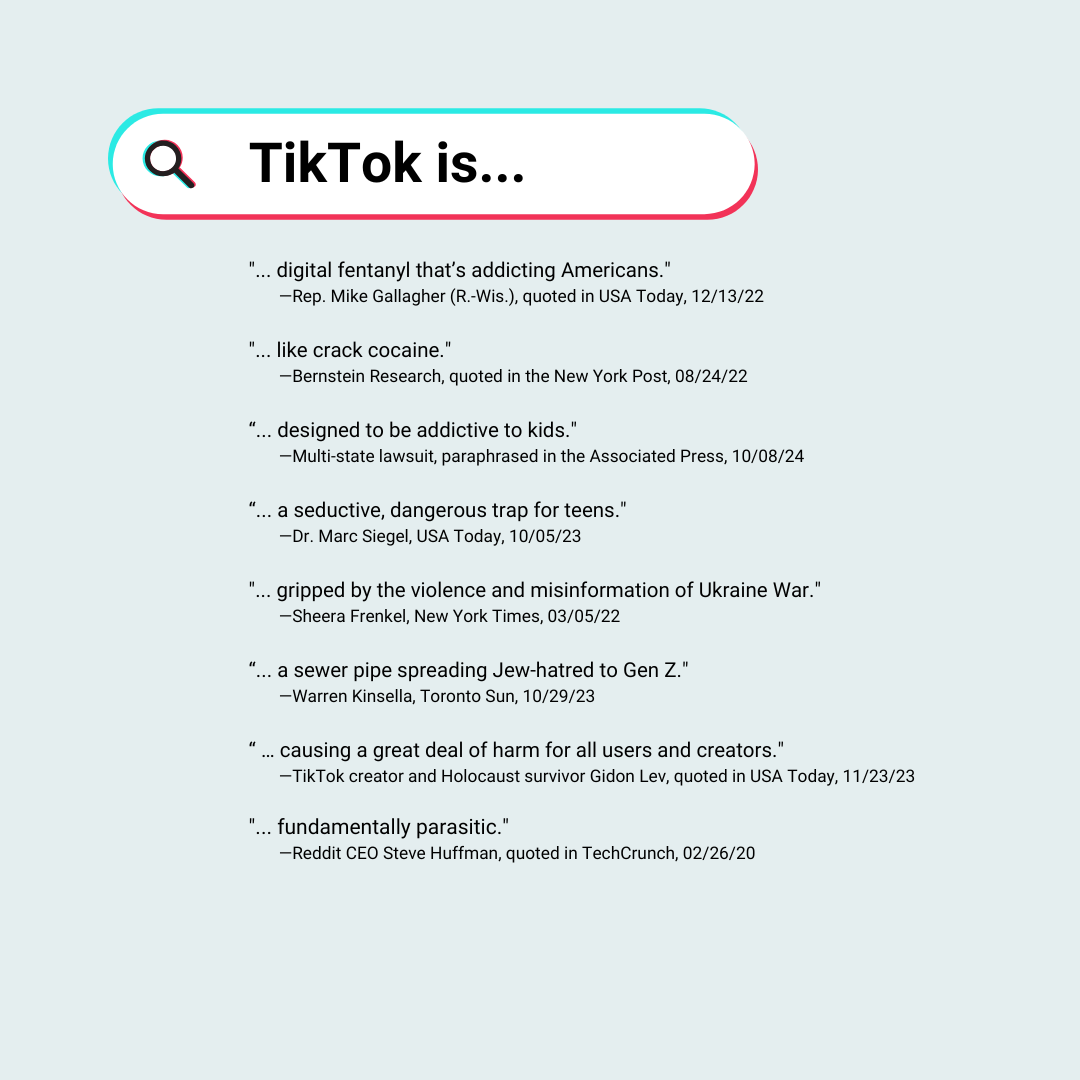

FYI: This essay is drawn from a corpus of more than 10,000 articles, blog posts, academic studies, press releases and transcripts that published since 2018 and contain the phrase “TikTok is.” I compiled that spreadsheet with the database research tool ProQuest, then manually reviewed thousands of mentions.

Paid subscribers support this work; I’m a one-woman shop! If you value this essay and can afford it, please consider a paid subscription.

TikTok, we’re told, is an engine for culture: a hitmaker, a trendsetter, the zeitgeist in an app. It’s also curdling the brains of our slack-jawed teens and funneling our data to ~the Communists.~

In reality, I think, TikTok’s more of an enigma: a Rorschach blot that reflects back the prevailing concerns of its time and place. Because the app is so sprawling, and so prismatic, it makes a good vector for all kinds of larger social preoccupations.

From the very beginning, in August 2018, the public narrative around TikTok clearly mirrored the anxieties of the era. Early media coverage of the app described it as some kind of paradise: You find favorable comparisons to Facebook et al, and lots of wistful callbacks to Vine.

This was late 2018, remember, and Facebook, Twitter and YouTube hadn’t shed the stink of the 2016 election. Years later, analysts would theorize that TikTok’s rise was due in part “to the negativity on Facebook, including polarization and rampant misinformation.” Early TikTok looked so “pleasant,” in the words of one euphoric Kevin Roose review, because the rest of the internet looked so unpleasant. TikTok became a convenient foil.

Early critiques of the nascent app also reflected broader preoccupations. We’re now familiar, for instance, with allegations that TikTok’s Chinese ownership poses some national security threat. Regardless of whether that’s actually true, the claims tend to crop up at moments of heightened US-China tension: say, as US policymakers stepped up attempts to contain the Chinese tech sector, or as Trump lashed out at Chinese officials over the pandemic.

In 2023, when a Chinese spy balloon appeared mysteriously above Alaska, Republican lawmakers leveraged the event to argue that TikTok also posed some threat to Americans. “A big Chinese balloon in the sky and millions of Chinese TikTok balloons on our phones,” Sen. Mitt Romney tweeted.

By that time, TikTok had itself ballooned so much — and grown so central to online culture — that public and political discourse of the app routinely probed the depths of its supposed power. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, TikTok could boast only 40 million monthly users in the US. By June 2020, that figure had climbed to nearly 92 million as lockdown boredom and anxiety pushed millions of Americans to the app for the first time. News articles began ascribing profound influence to TikTok: first in music, then in almost every other aspect of US cultural and political life.

TikTok, in other words, “became” the culture — or at least a primary shaper of it. Accordingly, TikTok’s post-pandemic critics began blaming a number of wider cultural problems more directly on TikTok itself. That surfaced first in concerns for child safety, which initially involved the content on the app; by 2022, critics were arguing that TikTok’s very design actively worsened youth mental health.

One year later, after the October 7 attacks in Israel, critics also pilloried TikTok for purportedly favoring pro-Palestinian creators. But writing in The Washington Post that November, Drew Harwell and Taylor Lorenz came up with another, far likelier explanation: TikTok is so sprawling that its warrens contain a fabulous (unsettling?) range of perspectives.

If you’re looking for something on TikTok, in sum: You’re abundantly likely to find it. And that makes the app a convenient vehicle for all kinds of social narratives. It’s good and it’s bad; it’s a threat and a solace; it’s revving up culture and tearing it down.

And as of this writing, it’s going dark Sunday … though even that is uncertain right now.