Buy the damn ramen

An interview on the pressures of home cooking, before and during the pandemic, with the sociologist Joslyn Brenton

Hey friends —

It’s been a minute since we did one of these special editions, so I’m making this an extra-special one. It’s a transcript of an interview1 I did with the sociologist Dr. Joslyn Brenton back in March, for this really fun Kitchn story about how the pandemic changed American cooking. (Spoiler: It probably didn’t.)

Joslyn literally wrote the book on home cooking, with her colleagues Sarah Bowen and Sinikka Elliott, two years ago. “Pressure Cooker,” which you can read more about here, skewered the popular notion that every family (read: every mother) should aspire to homecooked meals every night — an impossible Rockwellian ideal that both liberal food reformers and conservative pundits have pushed for ages. (Bipartisanism at work!)

Joslyn’s take was, uh … not universally appreciated: “There were definitely some folks who had pretty nasty things to say about us online,” she told me last month. But in the context of the pandemic, in particular, her observations about the mythos and expectation and labor of homecooked meals have never felt more relevant.

As always, please let me know what you think of this special edition — you can hit “reply” or ping me on Twitter. And if this kind of thing interests you, you might also like our last two special editions: on the deceit at the heart of the “passion economy” and the unwitting diary in your Google searches. See you Friday!

— Caitlin

Hey, thanks for taking the time to talk to me. I laid this out in my email, but the story I’m working on is basically about the rise of home cooking during the pandemic, and I want to get your thoughts on that. But first I wanted to go back a little earlier. Can you kind of characterize for me the state of home cooking in America before the pandemic?

Joslyn: Sure. So basically, since the 1950s, we have seen a decline in home cooking. And when I say “decline in home cooking,” I mean “women spending less time in the kitchen,” because women have always been the ones doing the cooking in the U.S.

The 1950s were a time when women started entering the labor force en masse. White women, that is, because women of color were always in the workforce — first against their will as enslaved people, and later on in the homes of white women, feeding their children and cleaning their homes and helping their daily lives happen. But in the ‘50s, white women also entered the workforce. And they’re immediately confronted with this big problem: How do I work all day and come home at night and still do all the things I was doing before?

By the time we reach 2015, the average time Americans spend in the kitchen has been cut almost in half. But that’s not across the board — one of the myths about home-cooking, in general, is that poor people or working class people don’t cook. There’s this stereotype that they just eat McDonald’s. When you look at time-use research,2 though, we see that working-class women spend more time cooking than middle-class women. Because it’s cheaper to eat at home — McDonald’s is actually very expensive.

And what about the discourse around home cooking pre-pandemic? How would you characterize that conversation?

There’s a strong, pervasive, relentless discourse that good mothers cook. You can’t claim good mothering if you’re not cooking these meals from scratch, and every woman at this point knows that expectation and is trying to grapple with that expectation, which has just ramped up in the past two decades.

Now organic eating has come onto the scene. Or now it’s not enough to just feed your kid a meat, a potato and a vegetable, which used to be considered a healthy meal in the ‘80s — now parents are supposed to go above and beyond and repeatedly expose their children to healthy foods and develop their children’s palates.

Mothers are also getting a lot of messaging that the best meals are ones made from scratch with organic, local ingredients. That’s a standard only middle-class people have the time or the money to try to embody, and even they describe coming up short. It’s a very unrealistic standard that we’ve been steadily working up to over the past two decades. Especially for mothers, and especially for women.

Do you get the sense that gender dynamic has changed at all in the pandemic, or is it business as usual?

That’s what everybody wants to know. We know we had a fair amount of gender inequality with regards to cooking, cleaning and child-rearing before the pandemic. So far during the pandemic, there have been a lot of media stories on this topic,3 a lot of coverage that is anecdotal, talking to a handful of mothers. That’s valuable, but it’s not a research study.

The message coming across so far is that the pandemic has exacerbated gender inequality in several ways. Mothers working outside the home now have to deal with homeschooling children and dealing with the emotional labor of monitoring the family’s health, that kind of thing.

With cooking, I haven’t seen real clear data yet. I actually did just see a qualitative study that showed an uptick in men grocery shopping. Typically women do the grocery shopping. But one of the things this study found was that, for men, doing the grocery shopping in the pandemic was like, this performance of masculinity — they were out foraging for their families, downplaying the risks, out doing the shopping.4

When we look at these trends, we have to ask: Are people really trying to address gender inequalities, or is the work men are doing some offshoot of the masculinity that’s contributed to gender inequality all along? I haven’t seen a lot of really high quality research published on that yet, in part because the process takes so long.

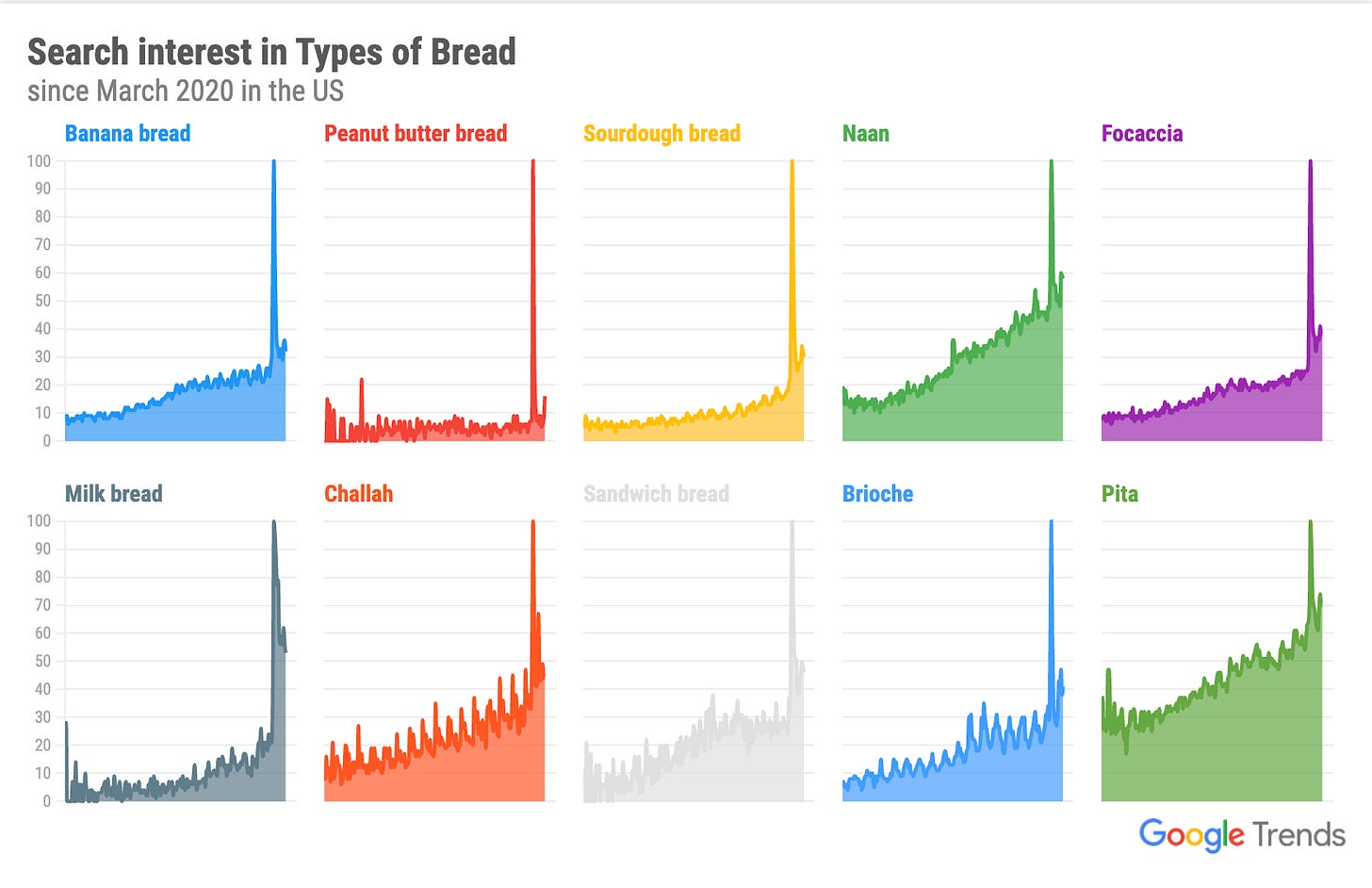

Can we talk a little bit about the amount of home cooking that people, women, have had to take up during the pandemic? There’s been a lot of discussion of this home-cooking “boom”: everyone’s cooking more, sourdough bread, etc. I’m curious, first of all, if it’s also your sense that this boom is universal — or if it’s concentrated among certain groups of people.

So immediately after the pandemic began I started noticing this. I’m firmly steeped in middle-class circles, to be sure, but one of the things I started seeing on Facebook was all this talk of sourdough bread. And the sociologist in me was like, “huh, this is really interesting.”5

I think one of the things we know we’re seeing is, yes, many people are cooking more at home — they have to. But we’re seeing that among middle-class people. It takes a long time to figure out how to make sourdough bread. It takes a lot of mental energy. One could argue it’s not especially expensive, but we know that with all food there’s a class component. The kind of foods we eat reflect a class status, a level of sophistication and knowledge. To me, a lot of this cooking from home stuff I’ve been seeing is very much a demonstration of middle-class status and also reflects middle-class privilege.

At the same time, you also see people posting sort of conflicting things on Facebook like, “is anybody else losing their minds? I’m sick of feeding the kids, my house is a mess. Who the hell are these people who have time for house projects?”

Would you expect this increase in home cooking, among middle-class families, to outlast the pandemic? Like is home-baked sourdough experiencing a long-term resurgence?

No, I don’t expect people to maintain this level of home cooking, because it’s physically impossible to cook when you’re working outside the home. I mean, in my house, we’ve tried recipes that you put on to braise at 10 a.m., and I keep an eye on it from the spare bedroom, and it’s ready to go at 6.6 I’ve definitely started dinner sooner than I normally would. Right now, we have those options. When people go back to physical workspaces, they’re going to be dealing with the same issues they have forever: How do I get a homecooked meal on the table if I don’t get home until 6 p.m.?

But there are a lot of unanswered questions still. There’s been this uptick in the use of Instacart and grocery delivery and pickup services, for instance, which is another middle-class phenomenon. There are always market solutions for people who have the money for them.

Also, what’s going to happen to the gender division of household labor? Have fathers been doing more in the pandemic, and might that shift after everybody goes back to work? Is this an opportunity for fathers to have some kind of emotional or cognitive reckoning, and will that change anything?

I think some really fascinating research is going to come out in the next year. In the next six months, I expect an explosion of research about what people were doing over this time. The optimistic part of me wants to feel like there’s a silver lining in this situation — that maybe this will change some longstanding inequities.7

As with all interviews I share here, this one has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. You would not want to read the whole rambling thing.

The icon in today’s header comes courtesy Rauan at the Noun Project.

This is a couple years out of date, but a fascinating breakdown of how much time different groups of people spend cooking.

At another point in our conversation, Joslyn specifically referenced this series in the New York Times about mothers and the pandemic.

In this same vein, I also read a v. telling report for this story by the market research firm Mintel that found men who cooked during the pandemic were far more likely to report it was for “leisure.” That’s not online for me to link to, alas — but it checks out, doesn’t it?

Across the pond, the food studies scholar Muzna Rahman had this to say about the pandemic sourdough craze: “In this unique moment in history, bread conveys several meanings. By baking it, we can reassure ourselves we are OK in lockdown because we can still access the sustaining pleasures of the domestic. The warmth and security it inspires are invaluable when our public spaces have been deemed dangerous. The agelessness of bread conveys the simplicity and knowability of the past, it roots us back into a recognizable narrative of history. This is a turn toward nostalgia – a looking back for a time that came before, a time that feels less uncertain.”

I grew up in an Italian family. My mother worked half of the time. Dinners where quick and tasty. There is something about traditional Italian cuisine that is efficient and good. Perhaps it's a tradition of peasant foods and recipes. You could do much of the heavy lifting on the weekend and that would get the hard work out of they way during the week. In the old days they jarred, preserved and had root cellars. In the modern age a freezer can go a long way. My wife who is Northern European and very American didn't grow up with these practices. As a result and for many other reasons I'm the cook of the house. My mother taught me the basics and I can follow a recipe so that has carried me through. I run an efficient inventory, I don't waste food, I cook proper portion sizes, I have great knives, good pots and pans, a thermometer, I run multiple timers and I buy good ingredients. Stop ordering out. Stop going to restaurants. If you go to a restaurant more that once a month it's excessive. (Who is going out to dinner during the pandemic anyway?) Take an online cooking class. Get a good chef's knife and learn how to keep it sharp. (Victorinox.) Buy good ingredients. They are not expensive especially when you cook for correct portion sizes. Stay out of the center isles of the supermarket. That's where all the processed food are. Don't buy any processed foods. Learn simple Italian or French dishes and build from there. It can be done with a little thought and preparation.

I'm only a recent subscriber but this was my favorite piece so far. I really appreciate the exposure to the sociological view here; without really giving conclusions about What Is The Truth about society but enabling me to question my assumptions about what I've been observing and experiencing. Thanks!