"This can happen to you"

Concerned moms mainstreamed trafficking myths that began with Q

I didn’t watch much of Sen. Katie Britt’s State of the Union rebuttal; her messianic smizing and breathy, high-pitched baby voice both made me viscerally uncomfortable. I did make it far enough, however, to catch the misappropriated, misconstrued trafficking anecdote for which Britt has since been rightly and roundly roasted: Lax border policies allowed a cartel to repeatedly rape a 12-year-old girl, she suggested.

The incident, while real, took place in Mexico during the second Bush administration. (To quote Scarlett Johansson’s excellent SNL cold open: “every detail about it is real — except the year, where it took place, and who was president when it happened.”) Because of those — ahem — minor factual inaccuracies, the story didn’t actually communicate anything about current border policies or immigration.

But *boy* did it say a lot about the cultural and political mainstreaming of Q-adjacent trafficking narratives — and the role that a certain type of concerned mom plays in popularizing and normalizing them.

Such narratives have only grown more prominent as QAnon has receded from public view. The right-wing conspiracy theory, an unwieldy amalgam of diverse political, religious and cultural myths, accepts (as a starting point!) that American “elites” maintain a secret market in stolen children.

The movement has quieted in recent years as social media platforms have moved to stamp it out. But its foundational belief — that stranger sex-trafficking represents a rampant, secretive, ever-present threat, across geographies and demographics — gradually leached into the mainstream during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Google searches about human trafficking spiked to an all-time high in July 2020, when a wild conspiracy about the retailer Wayfair took off with “people all along the political spectrum.” They’ve remained elevated ever since, buoyed in part by copycat conspiracies, the controversial film Sound of Freedom and a rising class of anti-trafficking influencers, many of them women.

“Different iterations of this trend have existed for well over a century … the idea of trafficking as a political cudgel is nothing new,” said Bond Benton, a professor of communications at Montclair State University in New Jersey who studies cultural narratives about trafficking and traffickers.

But the pandemic destabilized many people, he added, forcing them to view aspects of their lives in a newly precarious light. Things that felt certain, that felt safe, vanished or transmogrified overnight. Suddenly, you could die. You could lose your job. You could be “forced” to take a vaccine you didn’t want. You could be confined to your house for weeks on end. A stranger could sell your kids to a cartel. Why not?

The problem with these narratives, which bear little relation to how trafficking works in reality, is that they often erase actual survivors, misdirect resources and funding and advance social and political causes that have little to do with trafficking.

When Katie Britt told a survivor’s out-of-context story last week, she wasn’t advocating on the woman’s behalf — she was arguing for policies to shut out migrants.

‘Ladies, pay attention’

I discovered Benton and his partner/frequent co-author, Daniela Peterka-Benton, after reading an article they wrote for The Anti-Trafficking Review. In it, they chronicle the rise of “a seemingly new group of anti-trafficking ‘experts’” on social media who “call for concerned mothers to join the crusade” against ubiquitous sex traffickers. This crusade, they write, emerged from QAnon during the bowels of the pandemic — though it seems likely that many of its contemporary online supporters know little about those origins or politics.

Trafficking myths have, you see, been pretty thoroughly laundered by now. In my personal internet wanderings, I encounter them most often as “warnings” to savvy women and moms.

In one video posted last April, a manicured blonde woman warns that would-be kidnappers lie in wait under parked cars, hoping to slash your Achilles tendon.

In another, a different woman reports calling the police after spotting a plastic grocery bag tied to her truck. These two videos have 20 million views between them.

Other warnings advise women to watch for “telltale” signs of targeting, like zip ties on their door handles or pamphlets on their windshields. One recurring hoax warns that traffickers prowl suburban parking lots, marking the child occupants of each vehicle.

On a few occasions now, I’ve met these myths in real life — shared by concerned acquaintances or friends. They’re always meant helpfully, and reflect real fear, and it’s in that same spirit that I’ve tried to refute them. “Do you really think that happens at Walmart?” “Stranger abductions are actually really rare.” Online and off, I hear the same rejoinder: “It never hurts to be cautious.” But that’s not quite true, either.

Distorting reality

Pervasive misinformation about trafficking actually causes quite a lot of harm, much like misinformation in any other realm. In combination with wider conspiracies like QAnon, and political rhetoric like Britt’s (more on that later), these well-meaning social media crusaders have advanced misleading narratives that could further endanger victims, both Bentons said.

Take the simple issue of who gets trafficked, said Peterka-Benton, an associate professor of justice studies at Montclair and the academic director of the Global Center on Human Trafficking. Yes, “it can happen to anyone.” But that risk is not distributed evenly.

Trafficking victims are overwhelmingly people who are marginalized or vulnerable, including people of color, people living in poverty, undocumented immigrants, children living in the foster care system, people who are LGBTQ+ and people dealing with mental health illness, abuse or addiction. While social media narratives almost always center on women and girls, traffickers also target boys and men.

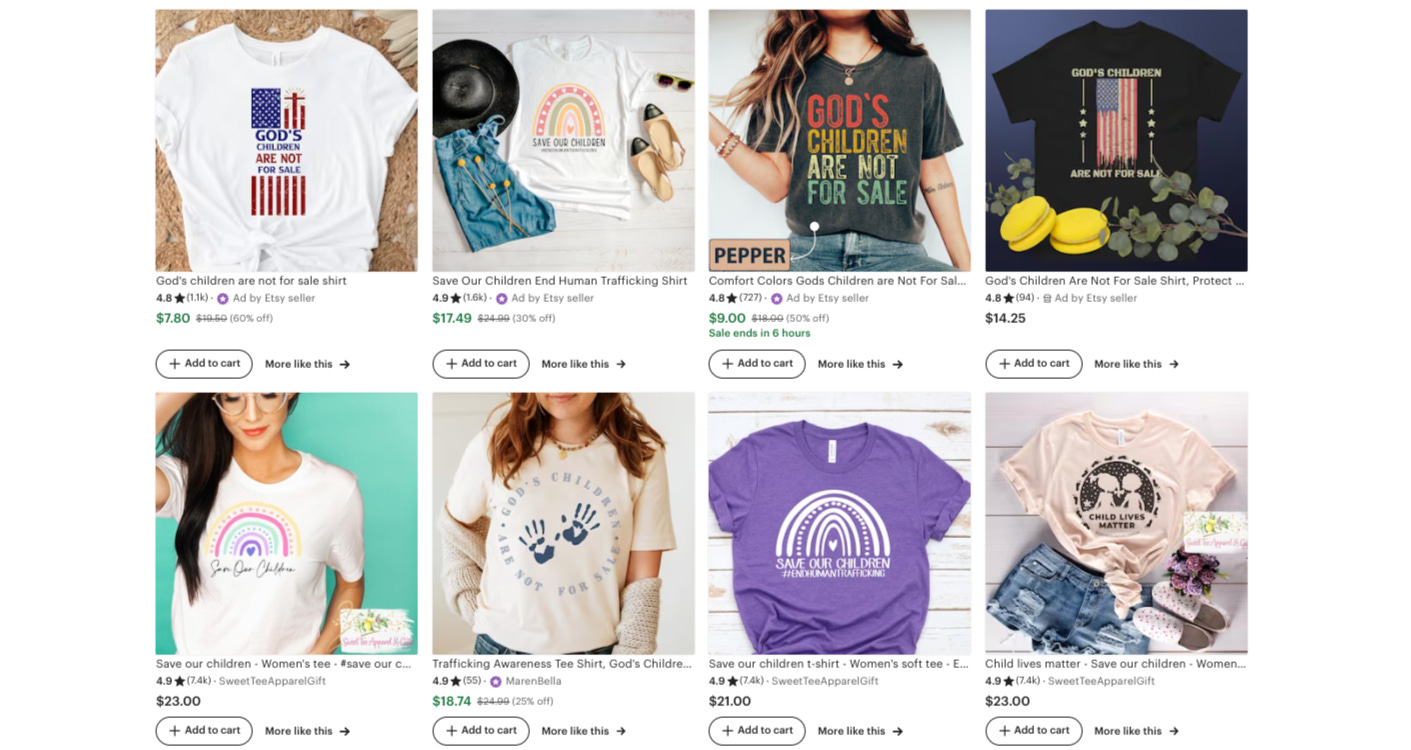

Traffickers also very rarely kidnap strangers, even children. In fact, child victims are overwhelmingly trafficked by relatives, neighbors or family friends. But even that single-minded focus on sex trafficking is a bit of a trap, because it ignores the vast, under-prosecuted scourge of forced labor. (Please find me the cheery, pastel shirt that champions God’s exploited farm workers.)

“It distorts the reality of human trafficking and that’s really, really problematic,” Peterka-Benton said. “It impacts public perception, policy, legislation, funding for research … The fact of the matter is that a lot of people will still be exploited and trafficked, and will not have the support or help they need, while some areas [of trafficking] get more attention.”

Increasingly, that attention also flows to unrelated political causes that far-right activists falsely link with trafficking. Since 2021, high-profile conservative commentators and politicians have terrorized the LGBTQ+ community with accusations of “child grooming.” More recently, the anti-abortion movement has also lobbied in favor of new “abortion trafficking” laws, though the practices they target (namely, helping pregnant minors access abortion without parental consent) don’t approach any official definition of “trafficking” I’ve ever read.

Then, of course, there’s the whole immigration discourse … a shambles unto itself. In the past year, Britt alone has linked border policy to sex trafficking on at least five occasions.

“Trafficking seems to be almost a touchstone now for anyone who wants to signal their issue is important,” Benton said. “It’s become a real ploy. What’s absent are the voices and experiences of authentic trafficking victims.”

I asked the Bentons what can be done about — *gestures vaguely* — all of this, though even speaking the question made me weary. I might as well ask for a cure to culture wars, to misinformation, to the whole writhing mess of “bespoke realities.”

Sex-trafficking scares, throughout U.S. history, have tapped into something instinctive, foundational and deeply, counter-intuitively comforting for many people, allowing them to rearrange the discomfort and anxiety of social change into winner-takes-all battles between good and evil.

Europe has attempted to legislate its way out: A sweeping digital services law passed last year requires social media companies to mitigate disinformation, though a similar law likely would not work in the United States. And in the absence of public policy, some social platforms have retreated from content moderation. Elon Musk has personally sanctioned Pizzagate.

More action by online platforms would help, Benton said, as would better media literacy, beginning with education in primary schools. (“It’s almost a cliched solution at this point,” he acknowledges, which … doesn’t sound too hopeful.) Both Bentons agree that greater awareness and media coverage would also aid both the misinformation problem and actual survivors.

But we need awareness of reality, they stressed, not a social media myth.

RIP my inbox. This marks my attempt!

Further reading

“A QAnon Con: How the Viral Wayfair Sex Trafficking Lie Hurt Real Kids,” by Jessica Contrera for The Washington Post (2021)

“Dissecting the #PizzaGate Conspiracy Theories,” by Gregor Aisch, Jon Huang and Cecilia Kang for The New York Times (2016)

“Truth as a Victim: The Challenge of Anti-Trafficking Education in the Age of Q,” by Bond Benton and Daniela Peterka-Benton for The Anti-Trafficking Review (2021)

“Loose Women or Lost Women: The Re-emergence of the Myth of White Slavery in Contemporary Discourses of Trafficking in Women,” by Jo Doezema for the International Studies Association (1999)

Weekend preview

I’m currently reading about deathbed visions, the appeal of mukbang, the digital platforms that connect us to our cities, the disappearance of Kate Middleton (... on heavy rotation, tbh) and the evolution of “virality.” What are YOU reading?

Until the weekend! Warmest virtual regards,

Caitlin

The very last thing you probably want to do is to read more about #KateGate2024 BUT I found this article over at Nieman Lab written by a royal reporter to be super interesting: https://www.niemanlab.org/2024/03/this-is-just-weird-buzzfeed-news-former-royals-reporter-on-kate-middleton-palace-press-and-distrust-in-the-media/.

I have no idea what to believe but I'm really invested in this story.

You ought to consider talking to Becca Stevens, an Episcopal priest who runs Thistle Farms, a non-profit in Nashville for women survivors of trafficking and prostitution. She wrote a long post on Instagram when trafficking was in the headlines. Some Qanon people tried to shut her down in comments but she wasn't having it. She lives this every day and knows things. Anyway, great email today.